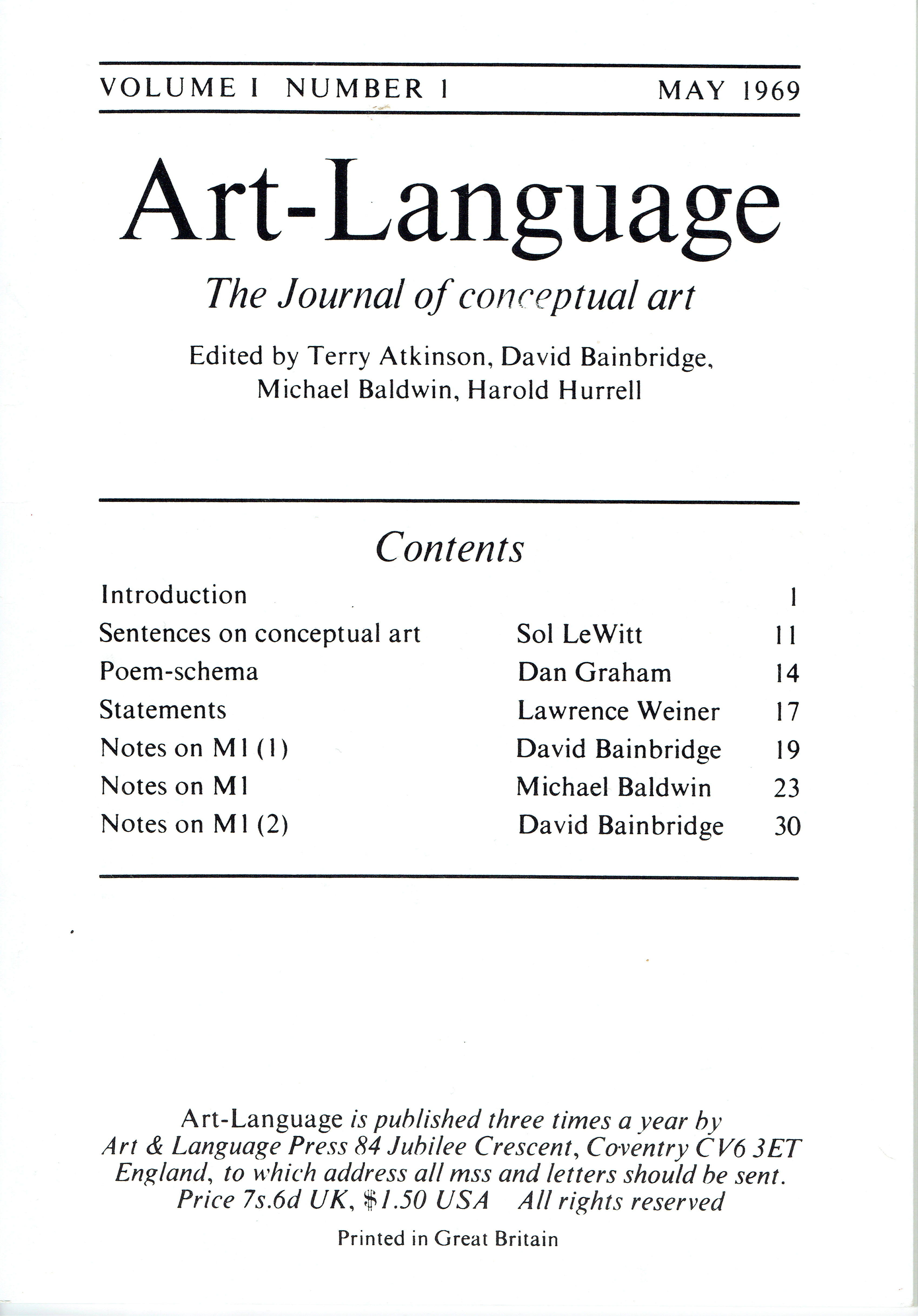

FROM ART-LANGUAGE THE JOURNAL OF CONCEPTUAL ART

TO ART & LANGUAGE

About twenty issues of the journal Art-Language The Journal of Conceptual Art have made it possible to develop a reflection on the very diverse forms that the work of art can take: poster, disc, video, printed text, flag and, of course, painting. The works of the years 1965-1967 materialize in the form of experiments or texts on canvas. During the years 1968-1972, a set of works took the form of annotated texts.

Art & Language is a movement created in England in 1968 according to the name of the newspaper. The collaboration between the founding artists, Terry Atkinson, David Bainbridge, Michael Baldwin and Harold Hurell began in 1966 when they were still teachers in England at the University of Coventry. The journal Art-Language – the first issue of which is entitled “The Journal of Conceptual Art” – was published in 1969. Between 1968 and 1982, more than fifty artists took part in the activities of the Art & Language movement, including New Yorkers Joseph Kosuth and Ian Burn. Later, Charles Harrison and Mel Ramsden joined them. Ten years after its creation, the Art & Language movement is undergoing profound changes. Two of its members, Mel Ramsden and Michael Baldwin, are now continuing the project.

AN AVANT GARDE MOVEMENT

Art & Language attaches fundamental importance to “discussion”, a shared conversation. This artistic movement creates both works and practices: debate, exchange, questioning, questioning… The works arise from exchanges between artists, from the desire to include the visitor in a practice and to question the social role of the work of art. Like the surrealist and Dadaist artistic movements, the works are there to provoke the spectator’s imagination.

In phase with the social, economic and technical upheavals of the 1960s, Conceptual Art marks the end of an era and a real turning point in Art History. From the very beginning, Art & Language has been critical of traditional forms of expression that have emerged from art history. Through their unprecedented and diverse production, they participated in the counter-culture movement specific to this period. Art & Language is at odds with the tradition that separates “profane” everyday life from the “sacred” world of museums.

WHAT IS CONCEPTUAL ART?

What is art? When does an object become a work of art? What is the role of the artist and the museum institution in this process?

These are the questions that are at the origin of the Art & Language movement.

Answers are provided through conversations, text works, publications, drawings, installations and paintings.

Conceptual Art desecrates the role of the artist and questions the conditions under which the work of art is created. It puts language back at the heart of the creative process. The intellectual progress of the project (sketches, studies, thoughts, conversations) does not necessarily lead to the creation of an object.

ART & LANGUAGE AND THE RED CRAYOLA

Since the 1970s, the Art & Language movement has also collaborated with a proto-punk rock group called The Red Crayola, notably for the album Corrected slogan. Two other albums are co-written with Art & Language. In September 2007, a new collaboration with Art & Language, Sighs trapped by liars, was launched.

Since 1995, Art & Language has also collaborated with the Jackson Pollock Bar, a contemporary theatre company that stages Art & Language texts through performances described as “theoretical installations”, where actors perform recorded texts in playback.

PERSONAL EXHIBITIONS

(selection)

- 1967 Hardware Show, Architectural Association, London. [archive]

- 1968 Dematerialisation Show, Ikon Gallery, London. [archive

- Vat 68, The Herbert Art Gallery, Coventry.

- 1969 Pinacotheca Gallery, Melbourne.

- 1971 The Air-Conditioning Show, Visual Arts Gallery, New York. [archive]

- Art & Language, Galerie Daniel Templon, Paris.

- Art & Language, Galleria Sperone, Torino.

- Tape Show: Exhibition of Lectures’, Dain Gallery, New York.

- Questionnaire, Galleria Daniel Templon, Milano.

- 1972 The Art & Language Institute, Galerie Daniel Templon, Paris [archive].

- Documenta Memorandum, Galerie Paul Maenz, Cologne. [archive]

- Analytical Art, Galerie Daniel Templon, Paris [archive]

- 1973 Index 002 Bxal, John Weber Gallery, New York. [archive]

- Art & Language, Galerie Paul Maenz, Cologne.

- Art & Language, Lisson Gallery, London.

- Annotations, Galerie Daniel Templon, Paris.

- 1974 Galleria Sperone, TurinGalerie Paul Maenz, Cologne.

- Art & Language, Galerie Bischofberger, Zürich.

- Art & Language, Galleria Schema, Florence.

- Art & Language, Lisson Gallery, London.

- Art & Language, Galerie MTL, Brussels.

- Art & Language, Studentski Kulturni Centar, Belgrade.

- 1975 New York <—> Australia, Art Gallery of New South Wales,Sydney, and the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

- Art & Language, Foksal Gallery, Warsaw.

- Dialectical Materialism, Galleria Schema, Florence.

- Art & Language, Galerie Ghislain Mollet-Viéville, Paris.

- Art & Language, Galerie MTL, Brussels.

- ‘Piggy-Cur-Perfect’, Auckland City Art Gallery, Auckland.

- Music-Language, John Weber Gallery, New York.

- 1976 Music-Language, Galerie Eric Fabre, Paris.

- Art & Language, Museum of Modern Art, Oxford. [archive]

- 1977 10 Posters: Illustrations for Art-Language, Robert Self Gallery, London.

- Music-Language, Galleria Lia Rumma, Rome et Naples

- 1978 Flags for Organisations, Cultureel Informatief Centrum, Ghent.

- Flags for Organisations, Lisson Gallery, London. [archive]

- 1979 Ils donnent leur sang ; donnez votre travail, Galerie Eric Fabre, Paris.

- 1980 Portraits of V.I. Lenin in the Style of Jackson Pollock, University Gallery, Leeds.

- Portraits of V.I. Lenin in the Style of Jackson Pollock, Lisson Gallery, London

- Portraits of V.I. Lenin in the Style of Jackson Pollock, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven. [archive]

- 1981 Portraits of V.I. Lenin in the Style of Jackson Pollock, Centre d’art contemporain, Genève.

- Gustave Courbet “Burial at Ornans” Expressing, Galerie Eric Fabre, Paris.

- 1982 Index : Studio at 3 Wesley Place Painted by Mouth, De Veeshal, Middelburg. [archive]

- Art & Language retrospective, Musée d’Art Moderne, Toulon [archive].

- 1983 Index : Studio at 3 Wesley Place I, II, III, IV, Gewald, Ghent.

- 1986 Confessions : Incidents in a Museum, Lisson Gallery, London. [archive]

- 1987 Art & Language : The Paintings, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels [archive].

- 1990 Hostages XXIV-XXXV, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York. [archive]

- 1993 Art & Language, Galerie Nationale du Jeu de Paume, Paris. [archive]

- 1995 Art & Language and Luhmann, Kunstraum, Vienna. [archive]

- 1996 Sighs Trapped by Liars, Galerie de Paris, Paris.

- 1999 Art & Language in Practice, Fundacio Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona. [archive]

- Cinco ensayos, Galerià Juana de Aizpuru, Madrid. [archive]

- The Artist out of Work : Art & Language 1972-1981, P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, New York. [archive]

- 2000 Art & Language & Luhmann No.2, ZKM, Karlsruhe. [archive]

- 2002 Too Dark to Read : Motifs Rétrospectifs, Musée d’art moderne de Lille Métropole, Villeneuve d’Ascq. [archive]

- 2003 Art & Language, Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Zurich. [archive]

- 2004 Art & Language, CAC Màlaga, Màlaga [archive].

- 2005 Hard to Say When, Lisson Gallery, London. [archive]

- 2006 Il ne reste qu’à chanter, Galerie de l’Erban, Nantes [archive] (Miroirs, 1965, Karaoke, 1975-2005) et Château de la Bainerie (travaux 1965-2005), Tiercé.

- 2008 Brouillages/Blurrings, Galerie Taddeus Ropac, Paris. [archive]

- 2009 Art & Language, Espoo Museum of Modern Art, Helsinki [archive].

- 2010 Portraits and a Dream, Lisson Gallery, London. [archive]

- Art & Language, Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago [archive].

- 2011 Badges, Mulier Mulier Gallery, Knokke. [archive]

- 2013 Letters to the Red Krayola, Kadel Wilborn Gallery, Düsseldorf. [archive]

- Art & Language, Museum Dhont-Dhaenens, Deurle. [archive]

- Art & Language, Garage Cosmos, Brussels.

- 2014 Art & Language Uncompleted : The Philippe Méaille Collection, MACBA, Barcelona [archive].

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

- 1968 Language II, Dwan Gallery, London. [archive]

- 1969 March, catalogue-exposition, Seth Siegelaub, New York. [archive]

- 1970 Conceptual Art And Conceptual Aspects, New York Cultural Center, New York.

- Information, Museum of Modern Art, [archive] New York.

- Idea Structures, Camden Art Centre, London [archive].

- 1971 The British Avant-Garde, New York Cultural Center, New York.

- 1972 Documenta 5, Museum Friedericianum, Kassel. [archive]

- The New Art, Hayward Gallery, London. [archive]

- 1973 Einige Frühe Beispiele Konzeptuelle Kunst Analytischen Charakters, Galerie Paul Maenz, Cologne [archive].

- Contemporanea, Rome.

- 1974 Projekt’74, Cologne.

- Kunst über Kunst, Kölnischer Kunstverein, Cologne. [archive]

- 1976 Drawing Now, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

- Biennale di Venezia, Venise. [archive]

- 1979 Un Certain Art Anglais, Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris, Paris. [archive]

- 1980 Kunst in Europa na 68, Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst, Ghent. [archive]

- 1982 Documenta 7, Museum Fridericianum [archive], Kassel.

- 1987 British Art of the Twentieth Century: The Modern Movement, Royal Academy, London. [archive]

- 1989 The Situationists International, 1957-1972, Musée National d’art moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris. [archive]

- L’art conceptuel, une perspective, Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris [archive]; Fundación Caja de Prensiones [archive], Madrid; Deichtorhallen, Hamburg [archive].

- 1992 Repetición/Transformación, Museo Nacional de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid. [archive]

- 1995 Toponimías (8) : ocho ideas del espacio, Fundación La Caixa, Madrid. [archive]

- Reconsidering the Object of Art, 1965-1975, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. [archive]

- 1997 Documenta 10, Museum Fridericianum, Kassel. [archive]

- 1999 Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin 1950s-1980s, Queens Museum of Art, New York. [archive]

- 2002 Iconoclash, Center for Art and Media (ZKM), Karlsruhe. [archive]

- 2003 Biennale di Venezia, Venise. [archive]

- 2004 Before the End (The Last Painting Show), Swiss Institute, New York. [archive]

- 2005 Collective Creativity, Kunsthalle Fridericianum, Kassel. [archive]

- 2006 Le Printemps de Septembre à Toulouse – Broken Lines, Toulouse.

- Magritte and Contemporary Art: The Treachery of Images, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles. [archive]

- 2007 Sympathy for the Devil: Art and Rock’n Roll since 1967, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. [archive]

- 2008 Vides. Une rétrospective, Musée National d’art moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris.

- 2009 Rock-Paper-Scissors, Pop Music as Subject of Visual Art, Kunsthaus, Graz. [archive]

- 2010 Algunas Obras A Ler – Collection Eric Fabre, Berardo Museum, Lisbon. [archive]

- Seconde main, Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris/ARC, Paris. [archive]

- 2011 Erre, Variations Labyrinthiques, Musée National d’art moderne, Centre Pompidou-Metz, Metz. [archive]

- 2012 Materialising ‘Six Years’: Lucy Lippard and the Emergence of Conceptual Art, Brooklyn museum, New York. [archive]

- 2013 As if it could . Works and Documents from the Herbert Foundation, Herbert Foundation, Ghent. [archive]

- 2014 Propanganda für die Wirklichkeit, Museum Morsbroich, Leverkusen [archive].

- Critical Machines, American University, Beyrouth. [archive]

THE PHILIPPE MEAILLE COLLECTION AT CHATEAU DE MONTSOREAU, FRANCE, LOIRE VALLEY

Mirror Piece, 1965

“What interested us in mirrors was the fact that a mirror produces the image perfectly “transparent” “.(Art & Language)

Mirror Piece is a wall installation composed of a series of 20 mirrors of different sizes, on which regular or deforming glasses have been affixed. They are accompanied by a series of typed sheets of paper that invite you to compose groups of mirrors by size or reflection category.

This work is imbued with the dominant minimalist aesthetic of the time.

In this reflection on painting, the artist replaces it with a mirror and invites the visitor to identify the mirror, no longer by its usual function, but as an object of art in the museum environment.

Since the Renaissance, painting has often been compared to a window on the world, the central perspective allowing the viewer to evaluate what is contained within the image.

Art & Language reorients this century-old convention by replacing the surface of the painting with a mirror. Rather than looking at an image constructed by the artist, visitors are now confronted with their own reflection, thus questioning the notion of painting as a representation of reality.

Used by artists such as Velàsquez, Manet or Magritte but also in the tapestries of the Apocalypse of Angers, the mirror really took on a central role in artistic practices from the 20th century onwards. The avant-garde experiments of the 1920s, such as kinetic art, surrealism, cubist photography, use mirrors to take a different look at the world.

From the Second World War onwards, artistic trends such as Minimalism, Arte Povera and Conceptual Art, questioned the capacity for representation itself.

Art & Language engages in reflection around the subjects of painting, dissimulation, enigma and opacity. Their work with mirrors invites reflection around the act of seeing and looking and makes the visitor an actor of the work and no longer a simple viewer.

The Air Conditionning Show, 1966-1967

As the founding movement of conceptual art, Art & Language develops a radical artistic practice based on a fundamental re-reading of the relationship between art and language. For Art & Language, the work of art is determined not by its materiality or visibility but by its ability to be thought.

Considering the written description of a work and its possible realization in space as equivalent, The Air-Conditioning Show, conceived in 1966, first appeared in 1967 as an article in Arts Magazine [Michael Baldwin, “Remarks on Air-Conditioning”].

This text takes as its starting point a volume of air conditioning in the gallery space, and specifies that the rooms must be scrupulously left empty and white, dull and neutral. The aim is less to designate a new, more or less unusual object as a work of art than to question our most established certainties about the nature of art and its relationship to its context, both discursive and institutional.

Highlighting the institution’s context and environment, the grouping of disparate objects in a given place, The Air-Conditioning Show does not exhibit anything except the space itself and, in its specific case, the museum’s thermal regulation system.

Installation #1, Château de Montsoreau-Museum of contemporary art. Art & Language, The Air-Conditioning Show, 1966-67

Index : Now They Are, 1992

These are paintings that take on the appearance of paintings of the highest kind in late modernism. However, they have the colour of neoclassical skin. The direction of the anomaly increases when we notice that this surface is made of glass, a surface that reflects the viewer, including the viewer’s skin. In fact, the glass is placed on the surface of a barely visible canvas through the translucent layer of paint on the inside of the canvas. In the centre of this plaque is the inscription “Hello”. Does this conventional salute provide clues to what’s underneath? What is hidden underneath, on the surface of the canvas, is the image of a female torso, mainly of sexual organs. It is drawn from Courbet’s Origin of the World. The “Hello” says almost nothing. It only suggests the figure in a refracted oxymoron way. The word suggests the word, and the word a source. Hidden and headless cutting acquires a head. These tables require a series of departures and retrenchments. The image under the glass is hidden by a surface that is both the equivalent of a figure and the reflection of the viewer. The spectator practices seeing what is below. He or she is transformed into a voyeur. But is there a space in which he or she tries to see what is really irrecoverable, that is, the space between the inner surface of the glass and the surface of the canvas?

The one who looks sees little sees little, and yet he directly fixes everything that there is to see. He or she sees himself or herself seeing, both in the literal sense of being reflected, as a spectator, and in the figurative sense where he or she must think about the possibility that he or she has seen what is not supposed to be seen.

Index : Incident in a Museum XXII (The decade, 2003 -2013), 1986

“The museum’s paintings are allegories of containment. They also address the issue of cultural inclusion and exclusion. They are paintings from the Whitney Museum, a place from which we were artistically excluded (we are excluded in the ordinary sense by nationality). But we wanted to describe this place as that of exclusion in a much broader sense, a hermetically sealed place almost in the biological sense, where one only enters through the wilder space of fiction, a place where one enters equipped with special clothes that have not yet been invented… and yet, a place both containing and contained, in the figurative sense, accessible only in imagination as fiction… or text. »

The fetishism of the “after”, the driving force of transformed and unprocessed commercial modernism, actively denies the artist, and in a sense the consumer, access to his work. His work of now is by no means the work of now. She is temporarily excluded from her view, dislocated not by what she follows, but by what he could follow her.

How can we express this exclusion, how can we literally produce something that has not yet been separated from our power to produce and even less to see? What figure can be given to this sense of loss?

Predictive images are like fakes, always exemplary of the concerns of the moment of their production. They are images of the future and although they are intact portraits of the present, including the present modes of predictive thinking, their captions and they are impossible to invalidate, except in and by future events. As images alone, one could say that they are impossible to invalidate in absolute terms… and that as ridiculous as they are.

A very tenacious possibility (for laughs) was to make an Incident in a Museum that would have shown visitors wearing propelled shoes, etc. We even tried to find some kind of pictorial propulsion. But these illustrative futurological conventions are deadly.

We experimented with the dark mystery, the shadows and the allusion, we even asked our children to give us some ideas, but each time it looked like the fraudulently modernized Paris school. Why?

Finally, we tried to spell out “The Decade: 2003-2013” on a large blue canvas. These and other objects from the same period have an extraordinary aura that they share with embarrassing and quite large works. Like some of the most excellent examples of popular (television) culture, they test our ability to stay in the room, tormented, fascinated and teeth grinding.

The large blue canvas with yellow letters that announces “The Decade 2003-2013” has been walled up with construction plywood. These letters can be glanced at through holes drilled in the surface of this wall. These incomplete and insoluble fragments are the equivalent of the vision of the museum that those who are excluded from it have. To see what is inside (to have a vision of either the painting or what it depicts), the viewer must get very close to what is blocking it. However, this barrier also constitutes the surface of a painting – a painting that denies it access to the surface of another. In the struggle to see this hidden surface, the exterior plywood facade is the identifying feature of the work. Those who are excluded from the consumption and handling of Fine Arts are often confronted with the surface of a prestigious or significant container. This surface, which is what prevents them from seeing a place that exhibits: not only a cultural event but also an artistic production. However, this is a place of cultural manifestation that nevertheless rebuilds a mechanism of exclusion.